A history teacher’s guide to celebrating Black History Month in education.

It’s time to celebrate Black History Month!

This year’s theme for BHM is ‘Proud to Be’, an idea that dates back almost a century:

- In 1926, Carter Woodson first organised ‘Negro History Week’ in the USA, specifically to overcome the ‘idea of inferiority’ among black people whose rights and culture were still trampled upon.

- Since then, we have seen many black leaders emphasise pride in black history, heritage and culture. In Britain, the work of John La Rose and Sarah White started a movement in the 1960s to educate black children and adults which was focused on the ‘achievements’ of black people.

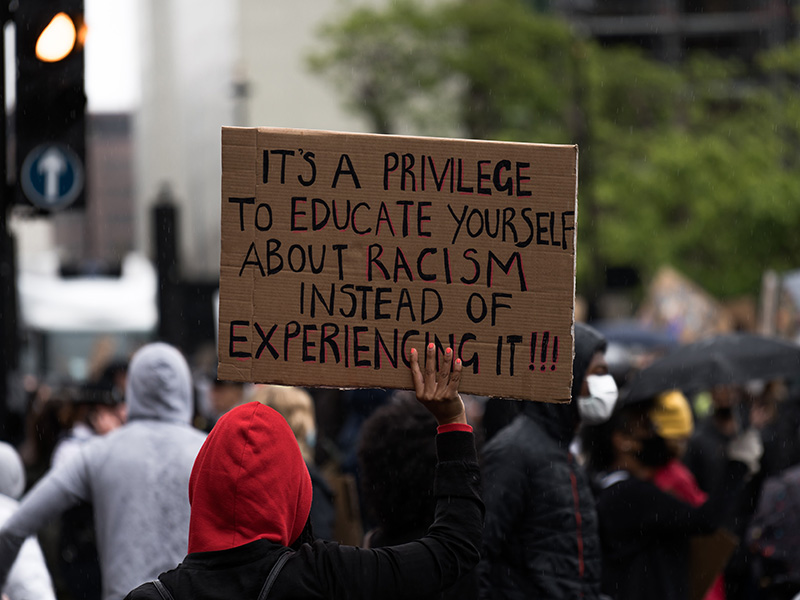

So, there is nothing new about the idea of promoting black history. In fact, it’s intertwined with a global history of activism, anti-racism and migration. But for younger generations, there was a notable shift in 2020, with worldwide Black Lives Matter protests giving hope for an anti-racist future and sparking commitment from many to educate ourselves about Black heritage and culture.

How has the Black Lives Matter movement changed things?

How we approach history in schools and as a nation has also been at the forefront of media attention since BLM protests in 2020 that went global following the murder of George Floyd in the US.

In the UK, the so-called ‘statue wars’ also prompted questions over how history should be remembered and taught – especially the history of colonialism and slavery. Many people objected to public space being taken up by statues of slave owners or imperialists. Here in Shrewsbury, over 5,000 people signed a petition to remove the statue of Shropshire-born Robert Clive who had a key role in engineering British rule in India.

Statue of Robert Clive in the centre of Shrewsbury.

What are some examples of how schools and colleges can celebrate black history?

In Shrewsbury, BHM is an important celebration. At Shrewsbury Colleges Group, 86% of students that left in 2020 were white and 2% were black. Compared to the national average, a much lower proportion of our students come from black and minority ethnic (BME) backgrounds. As a community, we have a responsibility to be inclusive and this means that those 2% black students see themselves represented in our lessons, on our display boards and as part of our syllabi. More than that, we enrich the lives of everybody in the college community by engaging with the diversity that is the reality of our country, and the world around us.

Students at college are keen to embrace diversity. This is shown through the Cultural Society that was started by students to experience and learn about different cultures and the traditions that take place around the world. Another group of students made suggestions to ‘decolonise the shelves’ in the Learning Resource Centre so that more non-white authors were represented. Within the history department, we reviewed our collection on the history of the British Empire which was disproportionately authored by white men.

In our community more widely, Shrewsbury is holding a number of events for Black History Month that we’re encouraging students and staff to attend. Patrick Vernon OBE will be speaking at Theatre Severn on 20th October. This should be a really interesting event for keen historians as Vernon has previously authored a book titled ‘100 Great Black Britons.’ Shrewsbury Museum & Art Gallery will also have a special exhibition about local connections to black history and the slave trade.

How can we improve our history courses to better include black history?

In the context of intense debates over how our national history should be remembered, teaching and learning in schools is more important than ever.

In the history department here at SCG:

- We encourage students to think about how the murder of George Floyd and the consequent global Black Lives Matter protests links to a long history of racial discrimination and brutality in the US. We point out that, even in the midst of a global pandemic, millions of people took part in these protests, including hundreds right here in Shrewsbury.

- We take inspiration from Ruby Bridges, who desegregated her school in Louisiana in 1960 and has been fighting for civil rights ever since. She still encourages young people to be anti-racist and recently expressed delight at the idea that “activism is cool again” among young people.

- In our British history course, we tell the story of the Windrush generation: crucial to Britain’s post-war successes, particularly the NHS, established in 1948.

- Our Global British History display board demonstrates Britain’s rich cultural heritage, fed by non-white people from around the globe. Historians have long been arguing that globalization is nothing new: the exchange of people, ideas, produce and culture is a story that goes back thousands of years. Miranda Kauffman’s Black Tudors show us that black people have been part of the UK’s history for far longer than most of us imagine. David Olusoga has suggested that York in Roman times may have been more ethnically diverse than York today.

SCG’s Global British History Display. In order to understand the world around us, we need to consider ourselves in a global context and we need to celebrate black history.

What can we do to continue celebrating black history beyond October?

Despite integrating these crucial moments in black history into our curriculum, we can always do more. Every year when BHM is celebrated we hear the same question: why only in October?

The fact is that history remains whitewashed in many British schools. Hannah Cusworth wrote in a recent article that only 10% of GCSE students study any black history.

There is also the issue in school curriculums and in our public history that black history often means talking about a history of racism and black people’s fight to overcome that racism. This is of course hugely important, and the black men and women involved in this fight deserve to be talked about.

However, we also need to be celebrating the achievements of black people in Britain and globally, thinking about a bigger picture in which black people are not downtrodden, struggling and surviving but flourishing, influencing and growing. Let’s talk about African history – how Mansa Musa is still the richest human that ever lived, how Yaa Asantewaa was a fierce warrior, how Kwame Nkrumah fostered pan-Africanism. Let’s give thanks for jazz music and rock n roll, for the sporting prowess of athletes like Simone Biles and for Aso-Ebi on the red carpet.

Finally, let’s avoid tokenism and bring black voices from history, alongside voices from ordinary black people, into every topic on our curriculum.